Uncategorized

Lord Delamere: The Godfather of Kenya’s Agricultural Economy

When Kenya attained independence in 1963, many white settlers opted to sell their farms and property and leave the country rather than submit to African rule. But not the Delameres.

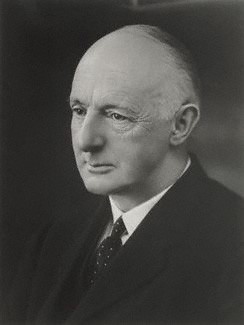

Hugh Cholmondeley, the 3rd Baron Delamere had died more than 3 decades earlier on 13 November 1931, but his heirs were just not ready to leave the newly independent country.

When colonial history is told, we often hear of the atrocities and the negatives. But modern day Kenya was built on the foundation laid by individuals like Lord Delamere. His arrival and that of the British in general may have been unwelcome, but his contribution was like no other past or present.

(Lord Delamere used to refer to the 3rd Lord Delamere)

Lord Delamere arrived in East Africa in 1897 for a hunting trip, in today’s Somalia. He fell in love with the lushness of the land and returned to the then British Somaliland four more times. He was at one time nearly mauled to death by a lion.

When he first set foot in Kenya, it was not on a mission to acquire land, but rather collect specimen for a museum back home. He arrived to a rude reception by both the Africans and the British.

“Sir, please take note that you are now on British soil. Any act of aggression on your part will be resisted,” read a letter he received from James Martin – a caravan master for Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEA).

He was later able to convince IBEA administrators that he had no ill motive, and in the process fell in love with the land.

He moved to Kenya permanently in 1901 accompanied by his new wife Lady Florence Anne Cole.

In May 1903, Delamere applied for a land grant from the British Crown but was denied. The Governor thought the land he requested was too far from any population centre. By then, British East Africa Protectorate was still relatively new and unpredictable. There weren’t enough administrative organs to govern the vast land properly.

Lord Delamere soon tried his luck again, submitting a request for 100,000 acres near modern day Naivasha. This too was denied as the government feared there might be conflicts with the Maasai who occupied the land.

Not one to give up, Delamere submitted another request and the government gave in to his persistence. He was given a 99-year lease on 100,000 acres of land that would be named ‘Equator Ranch’, requiring him to pay a £200 annual rent and to spend £5,000 on the land over the first five years of occupancy.

Adjusted for inflation, Delamere paid £22,000 (Sh2.9 million) annual rent, and was required to spend £550,000 (Sh72 million) on the land for the first 5 years. That was no small money, and few British could afford. But Delamere was an aristocrat.

He actually ended up spending 8 times more than he was officially required to, in his first 6 years (Sh575 million adjusted for inflation), ultimately sinking his Vale Royal Estate in Chesire London into receivership owing to an outstanding loan of £17,000 (Sh244 million adjusted for inflation).

In 1906, he made another land acquisition in Gilgil. This land would eventually include more than 50,000 acres and today still holds the name he gave it – Soysambu Ranch.

Settling in a country with no large scale organized agriculture and very low yielding crops and livestock breeds, Delamere was up for the challenge of his life. His next 10 or so years were full of trials and failures. He experimented relentlessly with crops and livestock accruing invaluable knowledge that served as the foundation of Kenya’s agricultural economy.

By 1905, Delamere was the pioneer in the East African Dairy Industry. He was also a pioneer at crossbreeding animals, beginning with sheep and chicken, then moving to cattle. He imported thousands of animals to improve the local breeds. Most of these succumbed to diseases such as foot and mouth and red water disease. He purchased Ryeland Rams from England to mate with 11,000 Maasai ewes, and in 1904, imported 500 pure-bred merino ewes from New Zealand. Four-fifths of the merino ewes quickly died.

Delamere eventually decided to grow wheat. Another experiment that went very wrong. The crop was plagued by disease, specifically Rust (fungus).

In 1909, Delamere was out of money. His last hopes rested on wheat planted on 1200 acres. As fate would have it, that too failed now leaving him totally broke.

Having rich and powerful friends back in England helped and Lord Delamere was soon back on his feet again. He created a ‘wheat laboratory’ on his farm, employing scientists to manufacture hardy wheat varieties for the Kenyan highlands.

To supplement his income, he even tried raising ostriches for their feathers, importing incubators from Europe; this venture also failed with the advent of the motor car and the decline in fashion of feathered hats.

Things soon started to look up for Delamere. He became the first European to start a maize farm, Florida Farm, in the Rongai Valley, and established the first flour mill in Kenya. By 1914, his venture started generating a profit.

When he started experiencing success in agriculture, Delamere began actively recruiting settlers to East Africa, promising new colonists 640 acres. At least 200 people responded.

He also successfully persuaded some of his rich friends to buy large estates like his own and take up life in Kenya. He is also credited with founding the Happy Valley Set – a clique of well-off British colonials whose pleasure-seeking habits eventually took the form of drug-taking and wife-swapping.

Delamere was also known for ‘childish’ antics like knocking golf balls onto the roof of Muthaiga Country Club and then climbing up to retrieve them. The story is often told of Delamere riding his horse into the dining room of Nairobi’s Norfolk Hotel and jumping over the tables.

One of his documented hobbies was vandalism. He would invite guests to a hotel he had built to break all panes, and later gladly foot the repair bill.

For 25 years, Delamere was the unofficial, undisputed leader and spokesman of the white settlers.

He died in November 1931 at age 61, having almost single-handedly built Kenya’s agricultural economy into one of the most stable in Africa.

He also left behind £500,000 (Sh3.9 billion adjusted for inflation) in unpaid bank loans.

In 1932, Nairobi’s sixth Avenue was named Delamere Avenue to commemorate his place in the development of the colony, and an eight-foot bronze statue erected at the street’s head, across from the New Stanley Hotel. The family however asked the government to remove the statue, and in its place a memorial of those who died in the world wars was erected.

This avenue was eventually renamed Kenyatta Avenue.

Sources – Wikipedia, Standard, EA Destination

Inflation Adjustor – Thisismoney.co.uk

Source: Nairobi Wire